On the Periphery of the New Lodge

On the Periphery of the New Lodge

The peripheral examination of the city is a firmly established method used by contemporary art practitioners examining the city; most recently in the exhibition ‘Live Cinema/Peripheral Stages’ by Bourouissa and Zielony curated by Vlas[1]. The exhibition deals with, “The social tensions inherent in living within the periphery of contemporary society. Defined as the edge or outskirts of an urban area, the periphery has become synonymous with under-resourced geographical regions.”[2]

The exhibition confronts the viewer with a sense of social and physical marginalisation as a result of beginning disenfranchised by the spaces that surround them. This is a tension that is evident in the New Lodge, verging close to the city centre, yet remaining on the edges of the society it is part of.

Following a number of walking studies along the periphery at night it became apparent just how charged tensions can become at the various entry points as I crossed the boundary from the familiar roads around the estate into the residential streets. Yet once inside the territory my fear was unmatched by the reality that I was confronted by. I found it considerably harder to photograph the interior of the territory, or begin to rationalise how this community has become disenfranchised from its surrounding landscape. Studies were conducted around the entries of the tower blocks, although the work was interesting, revealing layers of security measures around the doorways, the photograph lost its connection with the broader relationship to the territory. By stepping back from the core of the locality I got closer to isolating the relationships between two varying social spaces.

After subsequent visits a visceral friction remained at the entry points where these two varying social spaces collided. ‘The Edge of Darkness’ (fig.1) confronts the tensions that reside on the boundary, using the visual break between darkness and light to illustrate the boundary between city and territory. The low position of the tripod and yellow road markings draw the eye towards unfamiliar territory. In post-production the dark areas have been stripped bare of anything that would give the viewer any sense of depth, instead the road leads into an endless black space. An empty bottle and food carton sits on the cusp of light signifying the presence of a stranger somewhere behind the curtain of darkness.

fig. 1 The Edge of Darkness, Photograph, Fergus Jordan, 2011

The photograph characterises an overwhelming sense of mutual distrust. As the viewer stares into the darkness there is a creeping feeling that someone is staring back. Zurawski regards this spatial tension to be a result of living in a ‘culture of surveillance.’[3] Established systems of social control (street lighting, CCTV) collide with the vigilance of local communities, resulting in a combination of surveillance, counter surveillance and mutual surveillance practices. Everything that comes within visual range becomes occupied by a growing paranoia, positioning everything within the landscape in a panopticon power relationship between watcher and watched.

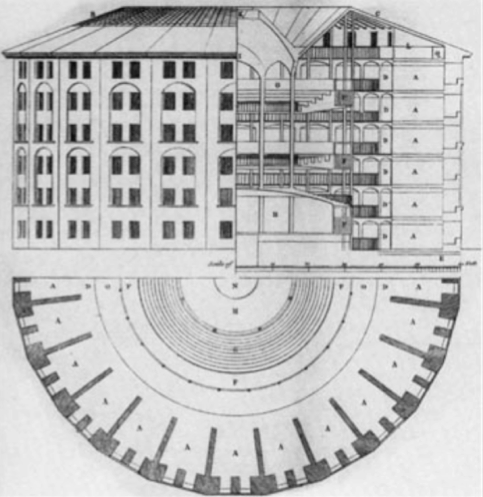

The panopticon model is the combined manipulative use of visibility (light) concealment (darkness) and positioning (the periphery and central core.) The concept of the panoptican was first theorised by Bentham in 1785 as a design for a prison, the building would be constructed in such a way as to allow the prison guards to observe the prisoners at all times, whilst disconnecting the prisoners’ view of the guards so they could never tell if a guard was watching (fig.2).

Fig.2 Panopticon, blueprint, Jeremy Bentham, 1791

Central to the design is the visibility of the inmates. The cells were positioned around the periphery of the building; on each cell door large windows exposed the prisoners effectively backlighting them. This gave full visibility to the prison guards monitoring the cells. In stark contrast the guards were positioned in a central tower, their presence would be concealed by darkness. Foucault described the function of the panopticon prison. “To induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power.”[4]

Foucault used the panopticon model to illustrate the practices of power that are present in surveillance societies; through the arrangement of space (physical objects) and vision (visibility and concealment) when a power relationship is developed between the watcher and the watched. Considering urban space as a panopticon has come under much criticism. The complexity and multitude of factors that make up surveillance practices in contemporary society arguably make it difficult to consider the panopticon model in relation to a city space.

Koskela points out, “The diversity of both spaces and social practices makes it impossible to consider urban space, simply and directly, as comparable to the panopticon”[5]

However the panoptic concept is not simply about one particular physical structure but about the correct alignment of space, darkness and light. Doherty’s video ‘Blackspot’ (fig.3) reveals this balance. The film overlooks Derry from the position of a surveillance camera during the last hours of light. As the landscape becomes darkened, the act of watching is rendered a futile. Tension mounts with the dimming scene, until the viewer loses all sensory control over what can now be observed. Only a disoriented landscape lit by the weakened streetlight remains, consequently this lack of visibility creates an overriding sense of anxiety.

I often found myself navigating space by the distinctive landmarks that surrounded me. Retaining a connection to these markers was a method to locate my position in unfamiliar streets. The seven tower blocks situated in the central core of the New Lodge provided a focal point to help me approximate how near or far I was from the centre. I began a series of photographs that documented my relationship with the towers. Which acted as a beacon to help me locate my position. This quickly became a paranoid relationship, if I could see the towers then perhaps others could see me? Their presence quickly became the focal point for a broader dialogue about the activities of mutual surveillance.

I began to frame the towers from a position where I felt most concealed from their physical dominance. In ‘On the Periphery of the New Lodge VIII’ (fig 4) the towers remain in partial view, creeping into the frame, peering over the roof of a row of terraced houses.

Fig.3 Blackspot, Film Still, Willie Doherty, 1997

Fig.4 On the Periphery of the New Lodge VIII, Photograph, Fergus Jordan, 2010

Following on from this approach I set out to visualise this sense of anxious paranoia, inducing the feeling of being under surveillance. Many of the spaces became the focal point for study are seemingly banal, striped of the situational uses of CCTV, security lights, In the absence of these mechanisms certain spaces still retained an uncomfortable sense of being observed.

‘On the Periphery of the New Lodge IX’ (Fig.5) presents an uncomfortable connection with a single window, the camera is positioned in the relative cover of darkness and the house is staged by a pool of light. The light source has been removed from the scene in an attempt to direct the viewer’s attention away from the light source itself toward the space that it is illuminated. This manipulation results in a staging of tension.

Fig.5 On the Periphery of the New Lodge IX, Photograph, Fergus Jordan, 2010

[1]Live Cinema/Peripheral Stages [accessed on December 8th 2011] <http://www.philamuseum.org/exhibitions/754.html?page=1>

[2]ibid

[3]Zurawski, N., I Know Where you Live! Aspects of Watching, Surveillance and Social Control in a Conflict Zone in Surveillance & Society (Northern Ireland 2005) 2(4) pp. 498-512.

[4] Foucault, M., Discipline and Punish the Birth of the Prison (New York: Vintage Books), p. 201

[5] Koskela, H., The Gaze Without Eyes: Video-Surveillance and the Changing Nature of Urban Space in, Progress in Human Geography (Helsinki, 2000) 24, (2) pp. 243–265

Written by Fergus Jordan, taken from the PhD thesis; Under Cover of Darkness, Photography, Territory and the City. 2012 (Research institute of Art and design and the Built Environment, Univeristy of Ulster)

If you would like to know more about this research drop me an email: hello@fergusjordan.com

You must be logged in to post a comment.

There are no comments