Colour and Territory

Colour and Territory

The capacity to visualise territory at night is a never-ending dynamic commanded by the placement of a streetlight. Both obstructing and supporting these symbols and in some cases even amplifying their presence. A practical selection is discussed considering how the spectrum of conditions, from darkness (total disconnection) half-light (partial visibility) to direct light (full visibility) can alter the reading of territory.

From total darkness to half-light, iconography becomes instantly transformed by the orange sodium streetlights that blanket the landscape, contaminating the natural colour of most objects within its range. Where the thin coat of orange light reaches the murals and flag colours become altered having a dramatic visual effect on the majority of sectarian symbolism. Typically these symbols are based around the official flags of the Irish Republic and the United Kingdom. Generally, sectarian symbols that are associated with Irish republicanism are green, white and orange, Loyalist communities relate to red, white and blue colours. The significance of these colours cannot be underestimated. Wherever they are painted, a tenuous psychological bond develops between the associated colours and these spaces. Gregory discusses a similar theory that outlines the cultural and emotional bonds we develop with colour, “We attach such importance to our perception of colour it is central to visual aesthetics, and profoundly affects our emotional state.”[1]

Such a similar bond is clearly evident between colour and territory; colour is an instinctive method to identify space. However, under street lighting the tones of these symbols alter significantly. Green and orange mainly retain thier potency with only white changing to yellow. Reds and blues become muddy almost black while whites become yellowish in tone, this is particularly evident in ‘Gateway’ (fig. 1). The photograph depicts a steel fence painted red, white and blue spans around thirty metres in length, confirming the space as loyalist territory. In the middle of the fence a streetlight blankets the area with a yellowish orange colour, significantly altering the markings on the fence and ultimately the significance of the symbol. The photograph reveals the volatility of the iconographic symbol as the message becomes so easily dislodged by a thin cast of orange light. The dialogue of power is shifted just enough to permit the viewer to step out of the familiar relationship with these symbols, leading to a closer interrogation of the territorial authority of these spaces. Objects of fear and authority become vulnerable as the cosmetic nature of these symbols are exposed. Under the street light this territory is left open and defenceless. Its unyielding perception suddenly feels unconvincing as the physical territory becomes flexible, moving only in relation to where adequate vision and the correct colour temperature sanctions a clear reading of the surrounding displays.

Fig.1 Gateway, Photograph, Fergus Jordan, 2009

This subversion of symbols under the streetlight can also support certain mechanisms of territory, in particular the flag, a common sight, hanging from lamp posts. On my lonely walks across the city, they are often the only life-like objects I encounter, unsettling my relationship with a given territory. The quiet melodrama of a flag waving rapidly across the path of a street light, projects large shadows downward on to the street below. The light magnifies the flag, while its jerky violent movement, mimics the threatening presence of a stranger. Like a scarecrow this absurd illusion instills a tangible sense of fear. The realisation that it is only a shadow presented me with a deep feeling of unease.

Photographing this scene proved to be difficult, given the rapid lively movement of the flag. Another manifestation developed in the process of attempting to isolate the shadow of the flag in the form of a blurring effect. This process is isolated in ‘Unknown Territories, Belfast V’ (fig.2) after a one-minute exposure as the flag starts to become obscured, colours and shapes overlap again and again. Slowly the camera records the symbols significance eroding. Corresponding to Sugimoto’s method “twice infinity” this subversion permits the viewer to step away from their assumed meanings of the subject and begin to see them in a new light. In this example the erosion of the symbol reveals the vulnerability of the territory itself and the bogus nature of the symbol.

Fig.2 Unknown Territories, Belfast,V, Photograph, Fergus Jordan, 2010

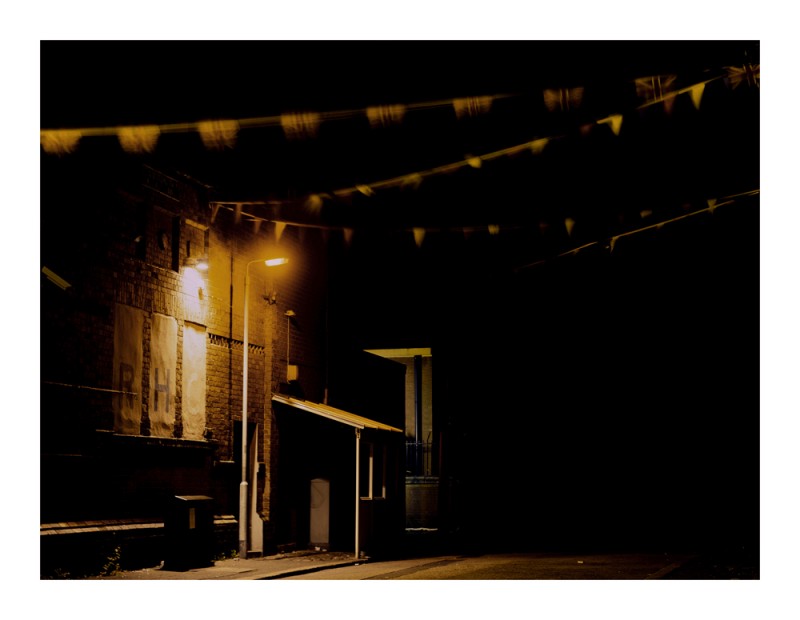

Given the precise conditions of light and placement, sectarian symbolism can become staged. These situations are rare, yet when it happens suddenly a territories presence is accentuated. ‘Enhanced Visibility’ (fig.3) studies this predicament. The street lamp emits a daylight temperature of light, displacing the landscape from the typical orange sodium streetlight that blankets the city. As a result the white light increases the visual range of the space, revealing the surrounding architecture in full colour. The photograph confronts the viewer with a pathway, drawing the eye towards a pool of white light shining downward onto a set of steps, where a feint Union is detected. Collectively the light and symbol expose the inhospitable nature of an otherwise anonymous space. What is perhaps most interesting about this scene is that the light is not only supporting the identity of the landscape, it is quite literally the torchbearer of control. The command of light retains the power to expose the identity of its surrounding territory but also the identity of any individual who wonders close to its path. As one gets closer to the light both identity and presence is given away, positioning the more vulnerable the individual becomes.

The use of high intensity light is a common sight in and around interface points. These are most often implemented where enhanced surveillance is necessary, as an institution attempts to take full control over the actions conducted within a given space. The light leads to increased surveillance practices, which in turn should lead to a reduction in crime and at the very least add to the perceived sense of safety in public space at night. However, it also leads to a sense of exposure and vulnerability.

Fig.3 Enhanced Visibility, Photograph, Fergus Jordan, 2009

The Omnipresent Light’ (fig.4) is a study of a children’s park situated in North Belfast. Each night the park is exposed by four high-powered security lights, directed into the park from a neighbouring police station, revealing a climbing frame perfectly. Red, blue, yellow and green sit against a wall of darkness isolating the object from its environment. The need to use such intensification, emulating daylight conditions at night suggests a fragile relationship between the park and its surroundings. Through light, the neighbouring police station in effect extending its presence and authority claiming the children’s park as its territory. Even though the photograph appears to be disconnected from the surrounding landscape, the light connects the park with the physical presence and authority of the police. The omnipresent light evokes authority. The complete elimination of privacy transforms the landscape into a place of suspicion, where a crime has or may be about to happen. The children’s park, a space of innocence and vulnerability, enters the adult realm of uncertainty.

[1] Gregory, R.L., Eye and brain the psychology of seeing. 5th edn. (New York: Princeton University Press, 1998), p.121

Written by Fergus Jordan, taken from the PhD thesis; Under Cover of Darkness, Photography, Territory and the City. 2012 (Research institute of Art and design and the Built Environment, Univeristy of Ulster)

If you would like to know more about this research drop me an email: hello@fergusjordan.com

You must be logged in to post a comment.

There are no comments